- Home

- João Almino

Free City Page 2

Free City Read online

Page 2

What feelings of longing are these that emerge from a happiness invented by memory? No, neither my mistrust nor doubts are of recent vintage, they were already present back when I was a boy, I just had to wait a few years to be able to perceive them. My desires have changed, my aspirations are different, I was successful once, before losing almost everything, but the hours pass just the same on different clocks, and the sun, facing the construction projects that filled the landscape, paints the morning with the same colors and conceals them, as always, at dusk. You, my lone, faithful follower on this blog, are right, why disturb what is quiet and forgotten?

On that first night when I met with Dad to clear up my doubts, he denied that he murdered Valdivino, it was a delicate thing for me to resurrect those old suspicions, and he told me that it was best to believe in the version told by the prophetess of the Garden of Salvation, Íris Quelemém, according to which Valdivino hadn’t died at all, and perhaps never would, he had always been an insomniac and a sleepwalker, and was still walking around aimlessly, walking day and night through the forest in search of Z, the lost city. Leave it be, João, those waters have passed us by.

Sometimes, as I was wrapped up in a daydream, our life in the Free City would invade my memory, a life made up of places and scenes, as well as Dad’s stories, and those of my aunts and the other characters around us—and of those others, mainly Valdivino’s—the things, facts, and people from my childhood arranged as if they were in an enormous family photograph, or on a chessboard in the distance where the distinctions between the pieces had dissolved into a uniformity imposed by time. Only Dad could, for the first time, reorganize the pieces on that board, and liberate my memory from that immobility. Fact is, he’s not dead, nobody killed him, Dad replied, he’s traveling or merely asleep, like Íris said.

A few years had passed since the incident occurred, when Dad returned to the Garden of Salvation, entering it anonymously, the Garden overgrown, and saw Íris enveloped in her white garment—long and wide, with puffy sleeves—flowing hair, blue ribbons running down her shoulders, beads around her arms and neck, big hoop earrings in her ears, and scarlet polish on her long fingernails, preaching at the top of Battle Hill, already with the bearing of the prophetess Íris Quelemém who would become famous throughout the Central Plateau, an indeterminate age in her round, wrinkle-free face and big, sharply radiant eyes, with the pensive air and unhurried voice of someone who was, at that moment, searching for inspiration for each of her words: From your venom shall flow the balm that will cure you; evil shall not grow within you, unless it be the evil that grows out of the conflict of your virtues, but if you’re lucky, you shall only have a single virtue; may it be tolerance or patience or love—words in which Dad could identify echoes of words he’d already read or heard. After everything that happened between Íris and Dad, it was to be expected that, at the very least, she would feel troubled by his presence. She looked at him at length and stopped speaking, thus creating a long, compelling silence.

On that first night, between four dingy white walls, Dad recounted the conversation he had with her. I came to talk about Valdivino, What took place is what was written, and Valdivino didn’t die, he’s still alive, she replied, Well, then, where can I find him? He is Karaí, the holy blessed Lord Master, but Taú and Keraná had seven children, the seven afflictions that shall fall upon the earth, and Valdivino’s wanderings are only the beginning of one of them; he is in the jungle, searching for Z.

On the day of the incident, April 22, 1960, the day after the inauguration of Brasília, Dad was urgently called to the Garden of Salvation, I remembered it well, since my memories of that day were very present for me, not only because of something that had happened earlier between me and Aunt Matilde, but also because Dad had traded his blue Willys jeep for a black ’46 Ford Coupe Convertible, in which he’d sped off that morning.

I distrusted what Dad told me on that first night, closed in between four walls, that Valdivino didn’t want any doctors to come, that it had to be him, Dad, he trusted Dad and nobody else, and that, when he arrived in the bedroom of a plywood shack in the Garden of Salvation, Valdivino was lying on the red dirt floor, wearing canvas pants, bracelets on his wrists, naked from the waist up, he had bruises on his head, perhaps from blows from a cudgel or something even heavier, he was delirious and stammered out a bunch of words that Dad tried to interpret. On the table there was a photograph of an adolescent girl whom Dad thought he recognized and a postcard from the city of Salvador, and a bottle of booze at the edge of it—oddly enough, since Valdivino didn’t drink. Nobody had seen or heard anything, He came to the Valley fleeing from creditors, said a stranger. Dad noticed that they were calling him Abel, He fell and hurt himself on his own, Sir, he drank too much of the ceremonial liquid, not sure if he did it on purpose, said another stranger, sticking his head in the window, then taking off soon after, and Dad never saw him again. Seems like you people around here are always just falling and hurting yourselves, Dad commented with a touch of sarcasm, recalling that he’d recently, at Valdivino’s request, come to Íris’s aid there in the Garden of Salvation and found her in a similar situation.

Dad suspected that the attacker was there in the room, he glanced around for anything that could serve as evidence, or at least a clue, all he found was a Continental cigarette butt on the ground, then he went over to Valdivino as he tried to utter a few words, delicately cradled his neck in his hands, and tried to lift his head. At that point it appeared to him that Valdivino had passed away, so he checked for a pulse and removed all doubt. That’s the first sin ever committed in the Garden of Salvation, an old man said to Dad, You mean the first crime?

Dad stayed a while longer in the Garden of Salvation, waiting for Íris Quelemém to receive him, until they came to tell him that Valdivino was still stretched out on the floor, Some say he’s dead, others that he’s still alive, so Dad started back towards Valdivino’s shack, but someone gave him a message that the prophetess requested that he leave, that she’d send for him if he was needed.

When Dad returned to the Garden of Salvation two days later, Íris told him, He’s a saint, to explain why Valdivino’s body wasn’t rotting. It will never rot, she prophesied, and she later spread word that Valdivino had been resurrected, that he was alive, although neither Dad nor anyone else at the house ever saw him again.

When she began to have her first visions, confirming the prophetic gifts that a mãe-de-santo had recognized in her, back when she still lived in Bahia, Íris had a revelation that Don Bosco had given her the mission to travel to the Central Plateau to help establish a new civilization, and she finally found her true path when, in November of 1959, she paid a visit to the widow Neiva Chaves Zelaya, better known as Aunt Neiva, a thirty-three-year-old truck driver who had recently founded the White Arrow Spiritist Union in the Gold Mountains, near Alexânia in the state of Goiás.

Bernardo Sayão is at the origins of many things, Dad told me, enclosed within four walls, for if it wasn’t for him, Aunt Neiva would never have come here, and we wouldn’t have either.

I’d like to thank my only follower on this blog for informing me that, in 1941, during the “March to the West,” President Getúlio Vargas had invited the agricultural engineer Bernardo Sayão Carvalho de Araújo to modernize agriculture in the Central-West, founding the National Agricultural Colony of Goiás in the São Patrício Valley, and Sayão had started from scratch, learning things there that he’d later employ in the creation of highways and the construction of Brasília. He brought machines and people from distant places to the uninhabited banks of the Das Almas River, which flows into the Tocantins River, built a highway connecting the Colony to Anápolis, a city of fifty-thousand people back then, a hundred and forty kilometers away, and built the Colony in the face of opposing bureaucrats, unafraid of inspections or administrative lawsuits, the city of Ceres eventually emerging out of the Colony, named as an homage to the goddess of grains.

None of

this is actually of interest, that Aunt Neiva lived on a farm in Jaguará, a city near Ceres, in the state of Goiás, and later lived in Ceres, and that Bernardo Sayão had been the best man when she married one of his trusted associates. If I include these details here, it’s only in order to satisfy my lone follower, who thinks the historical information he sent me is of fundamental importance. Maybe I’ll take out all this information when I reread this and just jump right to May of 1957, when Aunt Neiva, already a widow, was living in Goiânia, and Sayão invited her to join the others who were building Brasília. And it was the same with us, it all began with an invitation from Dr. Sayão, The story of Ceres explains a lot about Brasília, João, Dad told me, enclosed within four dingy white walls.

When Dad was a student in Belo Horizonte, my grandmother ran into serious financial difficulties and was unable to support him, but Dad didn’t abandon his studies and get a job because he received help from my other father, or rather, my biological father, a middle-class cousin who owned a farm near the Das Almas River in Goiás.

In Brazil in the Fifties, there were very few places that granted degrees in psychiatry. For people from Minas Gerais, after training in the hospitals and clinics of the capital, Belo Horizonte, the best option was to leave the state. Dad obtained a residency at the National Center for Mental Illness in Rio de Janeiro, where his younger sister, Aunt Matilde, a determined, fearless young woman, had just moved to start a job in one of the ministries of government.

When I lost my entire family—biological father, mother, and two older siblings—in a terrible accident—a subject, like many others, that I’d rather not discuss—Dad wrote to Aunt Francisca, my mom’s sister, to tell her that he wished to raise me. Aunt Francisca was against it, she didn’t want me to go to Rio, she knew that Dad had struggled with alcoholism since his failed marriage, she’d been raised to have rigid moral and religious principles and worried that an atheist like Dad would raise me with no religion, but the fact is that in a short time, at the age of six, I found myself living with Dad and Aunt Francisca, not in Rio de Janeiro, but in Ceres, in the state of Goiás. I’ll reveal only the ingredients of this long story: the end of Dad’s residency at the National Center for Mental Illness, my family’s farm near the Das Almas River, which Aunt Francisca had inherited, Dad’s bitterness, his desire to hide himself at the far ends of Brazil—despite the protestations of his sister, Aunt Matilde—and his ability to persuade Aunt Francisca that he had overcome his drinking problem and wanted to live a peaceful life managing the farm and helping to raise me.

After deep reflection, Aunt Francisca decided to take the risk, telling Dad in a letter that there’d be no lack of work for him in Ceres, that if he didn’t want to set up a psychiatric practice he could dedicate himself to another branch of medicine, since from the start the city had supported the healthcare industry, workers received free health care and the city already had two hospitals, with a third under construction, she didn’t care that others might think that they were living together as husband and wife, she was a righteous, principled woman and answered only to God. She only imposed one condition: that I be raised in the Catholic religion.

I reciprocated Aunt Francisca’s affection for me, and, at the beginning, Dad did more than just take on paternal authority, he was a companion to me, taking me on walks and talking to me about life.

Thus, we were living in Ceres when, one day, news spread that Dr. Bernardo Sayão, already vice-governor of Goiás and one of the directors of Newcap—the Company for the Urbanization of the New Capital of Brazil, which had been created through legislation on September 19th of that year, 1956—needed people to grow and cook food for those who were coming to build Brasília. He knew the disposition of the inhabitants of the Agricultural Colony and the experience they’d acquired in the production of foodstuffs, and for that reason he believed he could convince some of them to move to Brasília, together with people from Anápolis and Goiânia.

Aunt Francisca was the first to get excited about the idea, then Dad became convinced that it was an opportunity that couldn’t be passed up, and both of them spoke to me of a future that seemed to signify nothing less than happiness. The word “moving” danced endless, magical pirouettes through the skies of the future, but at first it didn’t capture my interest, perhaps because in Ceres—setting aside the great tragedy of my childhood—Aunt Francisca and Dad had shielded me from suffering, which I had heard about more than I’d actually experienced personally. I had everything and felt grateful for everything I had.

However, since the best thing I had was the love of Aunt Francisca, if she thought it good to leave, then I was delighted to accompany her. It was fortunate that Dad had wanted to live with us and take care of me, and that he’d instilled in me, at an early age, the notion that I should open my eyes to the vastness of a world that was much bigger than Ceres. The move was a door to that much vaster world, where wealth and happiness awaited us.

On this point I disagree with João Almino’s revision, with which he imbued our journey to the Central Plateau with too much wishful thinking. Therefore, I’m cutting out everything he added and retaining my original text, in which I merely state that, for Dad, the move would put his sense of adventure to the test and demand of him greater exertion than he’d ever before mustered. He thought about traveling through Goiânia or Anápolis, which was then the end of the line of the railroad that led to the southern half of the country, but at the time, as one of you readers of this blog astutely remembered, the Araguarina Company didn’t yet offer daily service between Goiânia and Anápolis, one hundred and thirty kilometers from the location where Brasília would be built, and even much later, up until the paved highway was inaugurated in 1958, the trip from Anápolis to Brasília was twelve hours through potholes and dust. We got there after a few days in Dad’s blue Willys jeep, sometimes cutting across terrain with no road, first heading towards Cabeceira Grande, where the Preto River serves as a border between the Federal District and the state of Minas Gerais, and from there we took the road to Unaí.

We found a plot of land when we got there, but there was a misunderstanding. Aunt Francisca was qualified to prepare food for the workers, but Dad wouldn’t be able to perform the tasks of an engineer that were wrongly expected of him and, although he could diagnose an illness here and there and care for the insane—after all, he’d spent two years in a psychiatric residency after he graduated—he decided that he didn’t want to dedicate himself to medicine. Unfit for the challenges of the times, yet conscious of the magnitude of what was being created on the Central Plateau, two days after we arrived he made a proposal to Bernardo Sayão, who, although he didn’t yet live in Brasília, was already directing all the principal operations there.

At the entrance to the land where the first campground was set up for the construction of the new capital, Sayão, stout, with a square, manly jaw, big ears, sharp eyes, a big, straight nose shaped like a perfect triangle, sweaty-faced, sunburned, expressively handsome, with voluminous hair parted at the side, seemed to my dad to stand two meters tall—later on Dad would come to find out that he was exactly one meter and eighty-six centimeters tall—and his fifty-five years didn’t show. Dad told him that he wasn’t an engineer, but that he would like to accompany the construction of the Goiânia-Brasília project, that he would dedicate himself to observing and recording everything, so that a detailed account of that epic endeavor might be published on the day of Brasília’s inauguration, written from the point of view of someone who lived the day-to-day of it, an official history of Brasília, which he called “The Golden Book,” from the start of construction up to its inauguration.

Sayão didn’t see any utility in the work of a scribe, since he had an aversion to idle chatter, I want practical people, ready to take on the jungle, look, Dr. Moacyr, it’s like I always say, all that’s possible to do has already been done, so we’ll do the impossible, but, perhaps even because he preferred action to chit-chat, he ended up

pragmatically accepting the presence of Dad and his notebook, not for the Goiânia-Brasília highway project, but during the construction of the two thousand-meter provisional runway of the future city, Just stay out of the way, he ordered.

When he revealed to Dad that President Juscelino Kubitschek was going to land there in a Brazilian Air Force plane on October 2 to visit the site that was selected the year before by the Commission for the Localization of the New Capital, Dad asked permission to record the visit in his notebooks. Sayão once again showed contempt for that inferior task, But come anyway, you can accompany the delegation, he said.

Dad carefully prepared for the visit, since he wanted to win the president over with his knowledge of the land and, thus, secure his position for good. At great cost, he acquired from Newcap a copy of the report that, towards the end of February in 1955, Donald J. Belcher had delivered to the Commission for the Localization of the New Capital, in which he read that “Brazil should be praised for the fact that it is the first nation in history to base the selection of the site of its capital on economic and scientific factors, as well as qualities of climate and beauty.” He drove his jeep to the Brown Ranch—which was called that because the location had been given the code name “brown,” which had beat out green, red, yellow, and blue, but which mainly corresponded to the Bananal Farm, which was adjacent to the Gama and Vicente Pires farms—and there sought out the junction with the existing roadways, the Anápolis-Planaltina road, which ran east-west through the proposed ranch, and the highway that connected Cristalina and Formosa to the south, verifying what Belcher had indicated in his report: “The distinguishing topographic feature is a triangular-shaped dome delineated by Deep Creek and the Bananal Stream where they come together to form the Paraná River, which then runs east toward the São Bartolomeu River.”

When the president, who had brought with him architect Oscar Niemeyer, was received by the governor of Goiás and Bernardo Sayão, Dad had already explored the vastness and transparency of that valley and accompanied them out to a cross that Sayão had fixed in the ground, and out to the Gama farm as well.

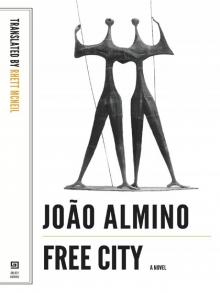

Free City

Free City The Book of Emotions

The Book of Emotions